Vocabulary & Choice of Words

Words are at the basis of all spoken and written expression. As information is conveyed to us chiefly through the spoken and written word, our capacity to acquire knowledge is limited by the size of our vocabulary.

VOCABULARY

Barrett Wendell defines vocabulary as the "total number of words at the disposal of a given individual."

Words are at the basis of all spoken and written expression. As information is conveyed to us chiefly through the spoken and written word, our capacity to acquire knowledge is limited by the size of our vocabulary. It follows that the more words we have at our command, the more ideas will we have, and the more accurately will we be able to express them. Hence the importance of the subject.

It is the purpose of this article to give in as brief and succinct form as possible some practical rules as to the most effective methods of acquiring a vocabulary, and a few general principles which will be helpful in arriving at a proper discrimination in the choice of words.

Says Professor Wendell: "The way to increase a vocabulary is very like the way to increase your personal acquaintance.

Put yourself in the way of meeting as many different phases of expressions as you can, read widely, talk with clever people." No more valuable or practical advice than this could be given.

Other rules which have been found useful are as follows:

Never let an unfamiliar word pass without thoroughly acquainting yourself with its derivation and meaning. Then do not let it lie idle or it will soon be forgotten. Use it or lose it.

The study of Latin, from which language thousands of English words have been derived, is commended.

If you are sufficiently familiar with some foreign language, practice translation. This is one of the best methods of strengthening a vocabulary. Translation of German into English is particularly recommended.

Some writers advocate the writing of verse as a profitable exercise in the selection of choice expressions.

In determining what words arc preferable we find the authorities at variance. Some lay down the rule dogmatically as to the preference to be given Saxon over Latin words, and small over large. Others assert that the selection should be guided solely by the purpose in writing, the effect desired to be produced, as long as the rules of good use are not violated. It certainly makes a difference whether our intention is to instruct or amuse.

The longer words are usually Latin; the shorter Saxon. While small words are more forcible and effective, the longer ones are more sonorous and elegant.

The use of foreign words and expressions, that is, their bodily transfer into the midst of an English composition, a fault to which the young and inexperienced arc especially prone, is condemned not only on the ground that it savors of affectation and pedantry, but also because there is no conceivable idea which can not adequately be expressed in English. The poet Bryant once told a literary tyro who had submitted to him a composition in which there were several foreign expressions, that the English language was capable of expressing any idea that he might form.

Care must also be taken to avoid the use of obsolete words, and words which arc so new as not to have obtained the sanction of good usage.

Again, to repeat that well-known quotation from Pope, "In words as fashions, the same rule will hold; Alike fantastic if too new or old; Be not the first by whom the new are tried, Nor yet the last to lay the old aside."

HINTS ON THE CHOICE OF WORDS

In his "Self-Cultivation in English," Professor Palmer tells us, "Our words should fit our thoughts like a glove, and be neither too wide nor too tight."

Accuracy of expression is one of the prime requisites of good style; but, like many other "gifts" of the writer, it is secured only by patient striving.

Before one can secure for his thoughts perfect fitting words it is necessary to know the exact meaning of each word. As a means of fixing these definitions in the memory, there is nothing better than a careful study of the derivation of words in general use, and of the history of words derived from proper names. How it revivifies our common words to see the pictures they presented to our Anglo-Saxon fathers—to find that our little daisy was, first, the day's eye, or that the dandelion was so called because its ragged edge resembled a lion's tooth (dent de lion). By a study of its origin, an interest, almost human, is given to such a word as boycott.

Another help is translation. He who can use the German for this purpose is especially fortunate. The similarity to the older forms of our language due to a common origin, impresses the English word more strongly upon the mind. The German is rich in compounds which must be translated by a phrase instead of a word. Also the shades of meaning afforded by the various prefixes of the verbs make necessary a painstaking accuracy and cultivate a discriminating power which is needed in choosing English verbs.

To retain those words already "ours to command" is not sufficient. There must be a systematic extension of the vocabulary, so that each sunset shall find the memory richer by at least a score of words.

Even when all these precautions have been taken there are words which will slip away in "the hour of need" and search must be made for the truants. Such a quest is tedious and one feels that it affords no scope for genius; yet it does, if it be true that "genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains."

Our language offers to the writer such a large assortment of "gloves" that no thought need go unfitted, nor need one accept "something just as good." By patient search the perfect fit may be secured.

Sometimes, though, this wealth of words is confusing and selection seems difficult. At such a time one must stop, look and listen. Yes, even listen, for frequently the sound of the spoken word reveals its appropriateness.

This sentence was noticed the other day, in a story in a leading paper. "It is needless to relate the luxurious interior of the apartments." The shade of meaning expressed by describe can not be expressed by relate. It is not always the verbs which prove the stumbling block. In the same article the expression, "as dead as the ashes of a mountain daisy," made the reader wonder how the dust of the daisy could be ashes unless the mountain was a volcano.

One should hold to the highest ideals even in the choice of words. Though in a limited sense it may be true, the writer must not admit to himself that "thought can be beyond the power of speech."

Read These Next

Self-Publishing Means Self-Marketing

There are many advantages to self-publishing, but nobody should make the mistake of thinking that it’s easy. Sometimes the writing and the publishing are the easy parts. When that is done the challenge is to put your work into the shop window, where others can see it. With over a million titles on the market, you are up against some stiff competition.

How Hardback Book Binding Works

Have you ever wondered how hardback book binding works? David Granoff explains how book printers and binderies put a hardcover book together.

Writing A Local History

Writing a local history can be a wise route for writers who wish to begin or expand their careers into a more scholarly non-fiction path. Whether the work is an article for a local publication, or a full book written for the community and beyond, local stories come with a built-in market eager to read material about the places around them and the people that used and inhabited those sites over time.

Self-Publishing For Dummies (For Dummies: Learning Made Easy)

Self-Publishing For Dummies (For Dummies: Learning Made Easy) Self Publishing To Amazon KDP In 2023 - A Beginners Guide To Selling E-books, Audiobooks & Paperbacks On Amazon, Audible & Beyond

Self Publishing To Amazon KDP In 2023 - A Beginners Guide To Selling E-books, Audiobooks & Paperbacks On Amazon, Audible & Beyond Self-Publishing: The Secret Guide To Becoming A Best Seller (Self Publishing Disruption Book 2)

Self-Publishing: The Secret Guide To Becoming A Best Seller (Self Publishing Disruption Book 2) How to Self-Publish Your Book: A Complete Guide to Writing, Editing, Marketing & Selling Your Own Book

How to Self-Publish Your Book: A Complete Guide to Writing, Editing, Marketing & Selling Your Own Book Self Publishing To Amazon KDP In 2024 - A Beginners Guide To Selling E-books, Audiobooks & Paperbacks On Amazon, Audible & Beyond

Self Publishing To Amazon KDP In 2024 - A Beginners Guide To Selling E-books, Audiobooks & Paperbacks On Amazon, Audible & Beyond Write. Publish. Repeat. (The No-Luck-Required Guide to Self-Publishing Success)

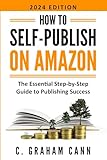

Write. Publish. Repeat. (The No-Luck-Required Guide to Self-Publishing Success) How to Self-Publish on Amazon: The Essential Step-by-Step Guide to Publishing Success

How to Self-Publish on Amazon: The Essential Step-by-Step Guide to Publishing Success 14 Steps to Self-Publishing a Book

14 Steps to Self-Publishing a Book How To Self-Publish A Children's Book: Everything You Need To Know To Write, Illustrate, Publish, And Market Your Paperback And Ebook

How To Self-Publish A Children's Book: Everything You Need To Know To Write, Illustrate, Publish, And Market Your Paperback And Ebook Self-Publisher's Legal Handbook: Updated Guide to Protecting Your Rights and Wallet

Self-Publisher's Legal Handbook: Updated Guide to Protecting Your Rights and Wallet